Montessori’s Approach to Language

Maria Montessori was a firm believer (backed up by scientific evidence) that a child is born with all he needs to acquire language. With that in mind, there are a variety of ways adults can support a young child’s language development, particularly by creating a conducive environment for language learning. At the very least, we know that if children are exposed to any language early in their development, they will learn to speak.

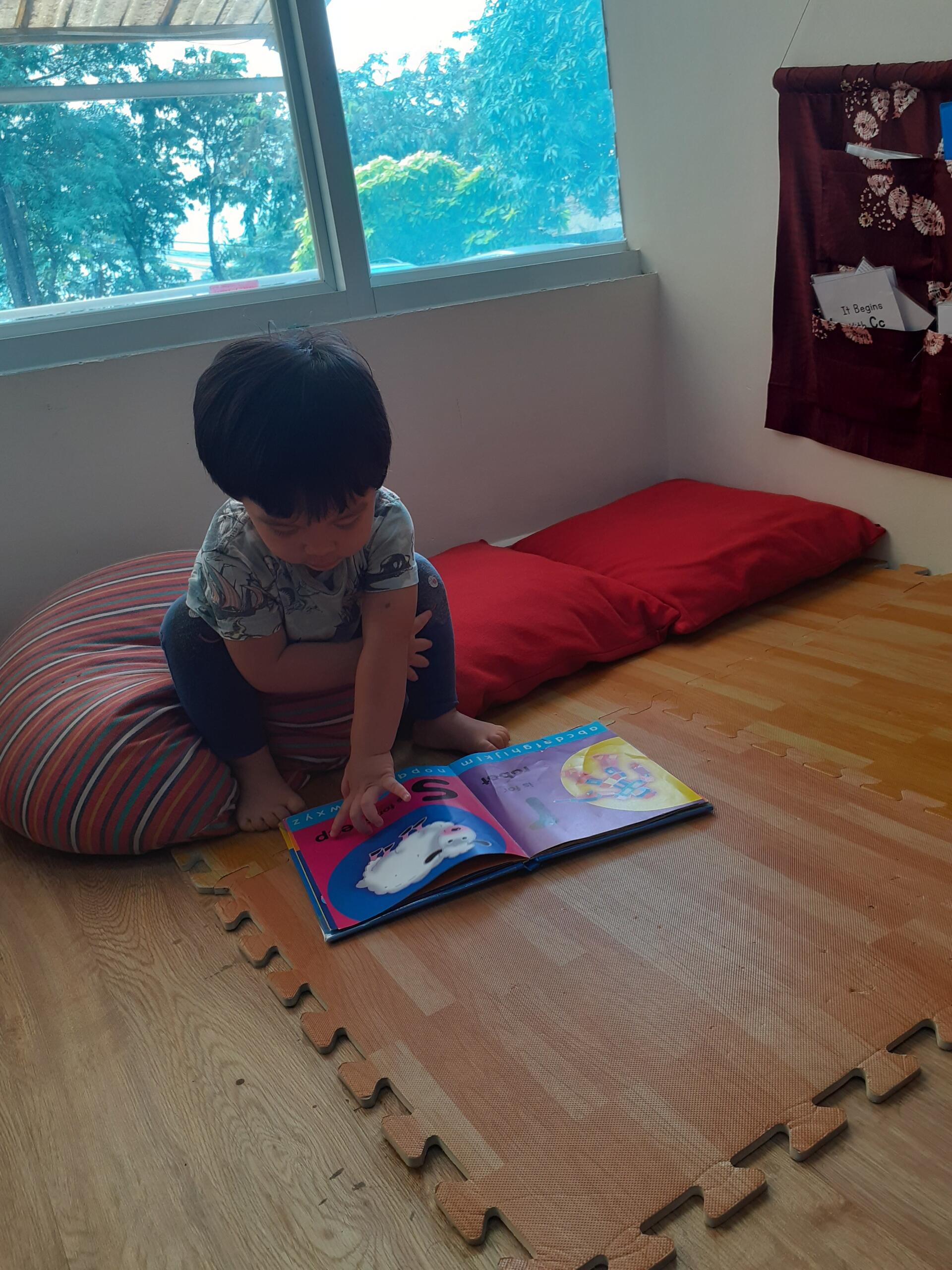

The youngster, on the other hand, must be taught to read and write. A child will pick up on the words that are presented to him in his environment. ‘Enters the grownup,’ says the narrator. We are in charge of the environment. As Montessori parents and teachers, it is critical that we curate and prepare the child’s environment for language development. To put it another way, to create this environment rich and full of opportunities for language learning.

We know that a child absorbs language with little effort when he or she is young. He develops an internal understanding of his surroundings. During this time, he must practice using these words. We can assist by repeating words, speaking clearly, and using words, particularly new words, in full sentences.

Language Development

The phrase “the absorbent mind,” coined by Dr. Maria Montessori, is well known. This concept is embodied in language acquisition. She wrote extensively about how children absorb their environments and, as a result, shape their brains unconsciously during the first three years of life, mapping language patterns simply by listening to us talk.

“From the moment of birth, infants know that spoken language comes from the mouth, and if we allow them the time, we will notice that when we talk to them, they try to move their mouths in a similar fashion,” says Silvana Montanaro. Even the most recent research backs up Montessori’s ideas:

“Studies show that children’s brains code information they see and hear from an early age. This happens on its own.”

As a result, the information available to a child in his environment has a significant impact on his language development. As a child grows older, he consciously leans into his environment in order to build on the knowledge he has gained earlier in life. The Montessori environment is designed to help children reach this stage. Adults facilitate learning by creating an environment conducive to conscious learning, as the adult can do for the unconscious stage, but he must also allow the child to discover his own language.

The Montessori Setting

The Montessori classroom prepares the child for literacy in two ways: through a well-prepared environment and through the teacher’s guidance. Dr. Montessori advocated for a well-prepared environment with a wide range of parameters. This leads to the next critical factor: allowing the child to develop at his or her own pace:

“When given the freedom to trust their own ears and judgments, many children demonstrate amazing facility as they begin to develop language.”

The materials in the classroom allow the child to direct his or her own learning, beginning with Practical Life. A child not only learns the fine motor skills required for pouring, but also develops focus and confidence as he learns to care for himself and the environment. As a result, the child develops a fondness for his surroundings. He wants to take care of it and learn more about the environment.

Language pervades every aspect of the classroom setting. The environment must support even the earliest attempts to write, whether it is play dough, pin punching, knobbed cylinders, metal insets, or tracing words. Furthermore, rather than having one “writing center,” a classroom should have multiple “writing centers.”

Materials isolate parts of the letter shape and parts of the word (the sounds) so that a child can progress to writing letters and reading on his or her own.

Montessori Language Resources

“Learning new words allows children to accurately label objects and people, learn new concepts, and communicate with others,” according to the language materials.

Language is a method of communication that allows the child to express himself and, if the adult allows it, to learn language.

A phonetic approach is use in Montessori classrooms. Furthermore, Dr. Montessori believed that language learning was a holistic developmental process that involved both the mind and the hand, with sensory development serving as a primary driver, at least initially, in a child’s language learning:

“The letter is learn by combining these two things, looking at the letter and touching it – that is, by combining visual and muscular impressions.”

When a child traces a sandpaper letter, he sounds out the letter or hears an adult sound out the letter. Even in Practical Life, he hears the sound as he pours rice from one small pitcher to another.

Adults should not, however, limit themselves to materials that have already been prepared for the classroom. There are several activities that can be use to extend a child’s learning, such as “I Spy” and reading aloud recommended books for isolating different sounds. Adults can also speak vehemently to children.

Limitations may include effective error control, for example, when the work involves spelling. We have to wait for the development milestone to appear because we adults do not correct the child when he misspells, especially if he is phonetically correct. He will correctly spell “cat,” but at his own pace. We must believe in the process. This is obviously a difficult concept for even the most effective educators, let alone parents, to accept as their children begin their language development journey.

Montessori’s Three-Period Lesson

During this time, the three-period lesson is extremely beneficial.

- Point to the object and say its name: “This is a pencil.”

- Then you can ask the child, “Show me the pencil.”

- Then, while pointing to the object, ask the child, “What is this?”

Common Parental and Teacher Misconceptions

The most common misconception is that a child should be able to read and write by a certain age. Some adults are unable to accept the range of development that occurs in typically developing children. Reading earlier is not always a good thing if the reading is force, memorize, or otherwise uninteresting to the child.

Perhaps she will learn earlier than her development would suggest, but one thing is certain: she will not be a lifelong reader and writer. Furthermore, as a result of the pressure and method used to learn a language, her communication skills may suffer.

As a child’s development progresses, he or she begins to understand that different letters and letter combinations produce different sounds. At this point, the child is no longer effortlessly absorbing; he must begin to organize what he has absorbed over the first three years. One example of how a child organizes his or her learning is the alphabet.

Adults can assist with songs, rhymes, and poems, as well as by tracking the words and sentences as we read books to him, playing I-Spy with letters and sounds, and encouraging the child to sound out words on his or her own. As he becomes more aware, he realizes that by putting letters together, we can create words.

Follow our fan page for more updates: